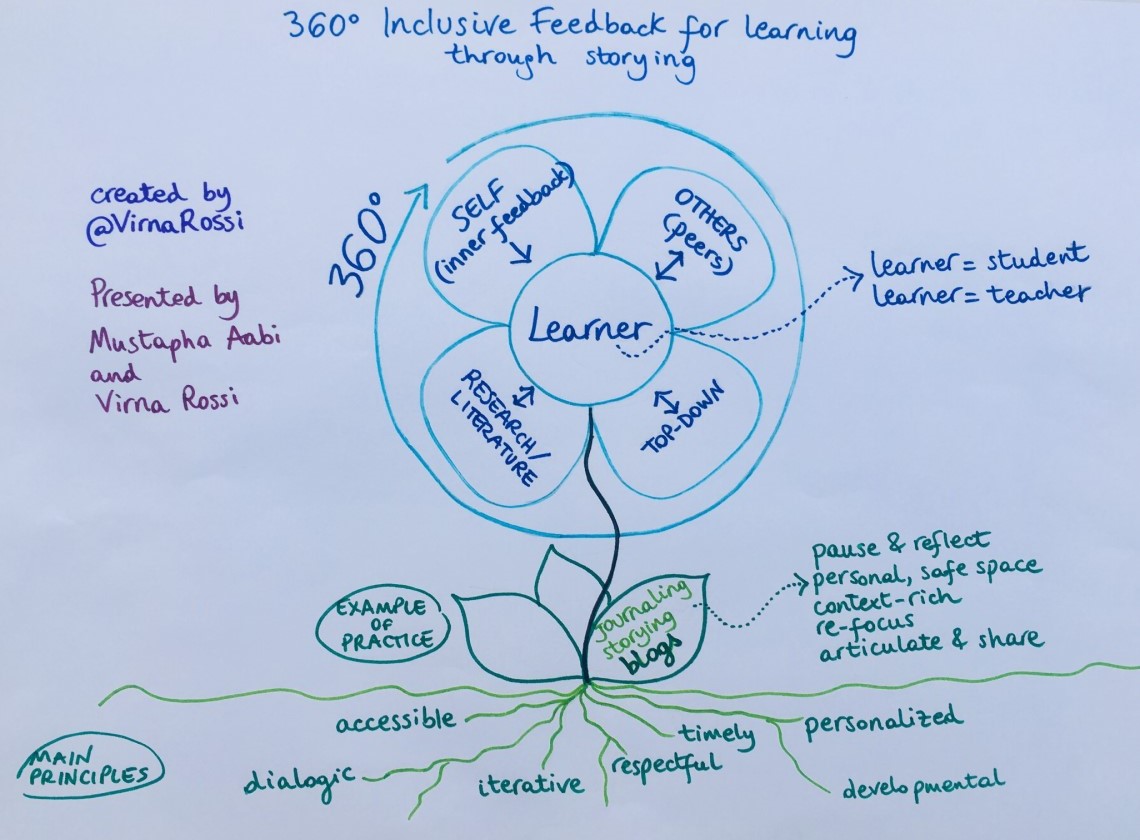

Inclusive feedback for learning is like a flower. A flower is both fragile and resilient. To thrive it needs good conditions, such as good soil.

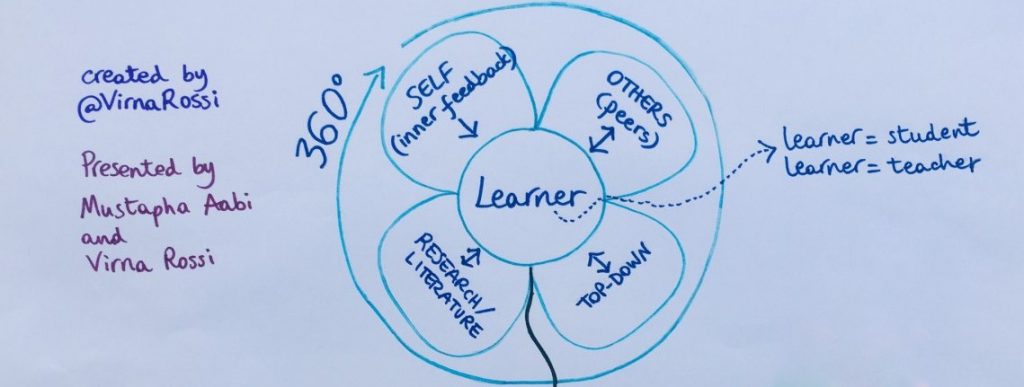

Who is the learner in the feedback process? It is the student. But it is also the teacher. Both students and teachers can thrive with inclusive feedback for learning.

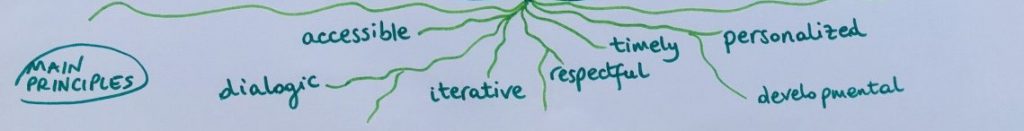

The roots

The roots of the feedback flower are the inclusive principles and values that underpin inclusive feedback practices such as:

- Accessible

- Dialogic

- Iterative

- Respectful

- Timely

- Personalised

- Developmental

The Petals

To be multidimensional, feedback should come from a variety of sources. In the flower analogy, these are the four petals which form the 360° wide-angle view.

Self

Inner feedback is very valuable to develop self-efficacy. We ‘talk to ourselves’ about our learning, during the learning experience as well as once it is completed. If we journal or blog – articulating our inner feedback – our ongoing inner narrative becomes more explicit and is more easily shareable.

Others

This is to enhance peer-learning. For students ‘others’ can be fellow students; for teachers, these can be colleagues and the students themselves.

Top-down

For students, this is feedback from teachers and other educators such as librarians. For teachers this is feedback from line-managers, principals or anyone ‘above’ them in their institution.

Research/literature

For the students, this the body of research of the discipline that they are studying: learning what the ‘experts’ in the field say – and discovering the present boundaries of the discipline – helps the students situate themselves within their field of study.

For teachers, engaging with current educational literature (generic or subject specific) provides indirect feedback on their own professional practice and expands their pedagogical horizon.

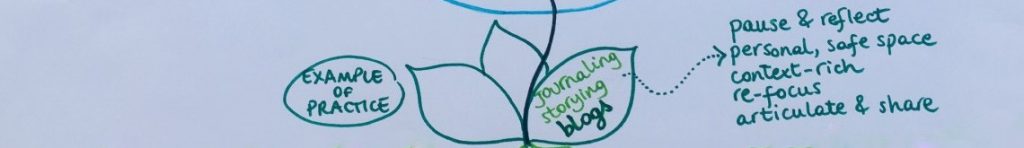

The Leaves

How, in practice, can we educators receive and give this type of inclusive feedback?

One very effective way in which the feedback flower can thrive, fed by inclusivity values, is through the use of journaling, storying and blogs (one of the leaves at the base of the flower). This applies to all disciplines.

Learning feedback activities such as these promote pausing and reflecting; they constitute a personal, safe space; they are context rich; they help learners re-focus, articulate and share their learning experience.

Journaling can effectively be integrated into the course. Teachers can plan a dedicated journaling time towards the end of every lesson: everyone is invited to blog or journal for about 15 minutes. Each student’s inner feedback written in the form of blog/journal can then be shared, discussed and used for ‘comparative’ learning. It can be used for formative and summative assessment submissions; it can also be part of an ongoing, life-long learning portfolio. And it constitutes very rich feedback for the teachers.

To build trust and truly model a learning mind-set, teachers should also journal at that same time: to articulate, record and share their inner feedback on the lesson, the cohort, their own learning, successes or missed opportunities in the learning that just took place. This enhances teachers’ feedback literacies.

The pandemic has accelerated and emphasised the need to review assessment and feedback processes. Teachers must design learning experiences that enable and enhance feedback literacies through inclusive, learner-driven processes. Feedback literacies are situated. The emphasis is now on engaging and learning from feedback – rather than simply about teachers giving ‘good’ feedback. For all these reasons, storying, journaling and blogging are powerful, effective ways to encourage 360° inclusive feedback for learning.

Find out more

Watch my 5 minute video below about the why/what/when/who/how of inclusive feedback: What best practice in feedback can I embed in e-learning?

References

Baughan, P., (2020) On Your Marks: Learner-Focused Feedback Practices and Feedback Literacy. [ebook] AdvanceHE. Available at: click here [Accessed 17 September 2020]

Nicol, D. (2019). Reconceptualising feedback as an internal not an external process. Italian Journal of Educational research, 71-84. Available at: click here [Accessed 17 September 2020]

Winstone, N. and Careless, D. (2019) Designing effective feedback processes in Higher Education, London: Routledge